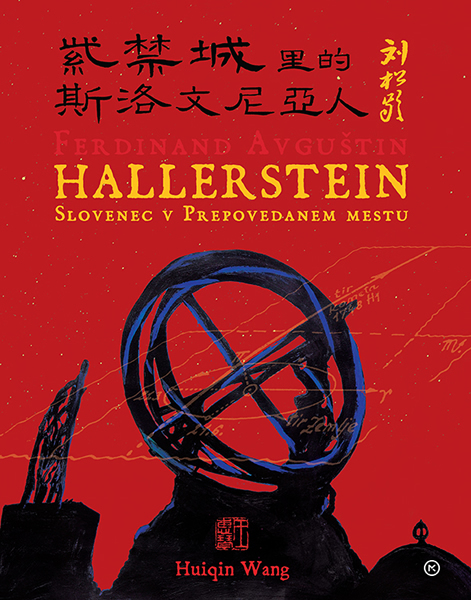

Ferdinand Avguštin Hallerstein: A Slovenian in the Forbidden City

Guest multimedia exhibition by Huiqin Wang

Slovene Ethnographic Msueum, 10 April – 4 May 2014

Ferdinand Avguštin Hallerstein – Liu Songling (1703 - 1774) is the renowned astronomist, a Jesuit missionary, scientist, inventor, mathematician, cartographer and diplomat, who was born in Ljubljana and lived for 36 years in China. He went to Beijing in 1739, where he worked at the Emperor's astronomical observatory and was awarded the title of Mandarin of the third grade. In addition to observing the stars and creating the calendar, he was in charge of the creation of an astronomic instrument or "sphere displaying the starry sky" and of the "great armillary sphere" that was completed in 1754, and was the largest, such instrument at the old Beijing astronomical observatory. He also discovered a new comet in 1748.

Creative Encounters Among the Stars

When Kublai Khan asked Marco Polo why he told stories about every other place but the one where he was born, the latter replied that every time he described a city, he also said something about Venice. If he actually spoke its name and everything he remembered about it, he could lose Venice and that was what he perhaps feared. “Memory’s images, once they are fixed in words, are erased,” said Polo. These lively discussions between the great ruler from the Far East and the imaginative Venetian traveller, so convincingly captured by the writer Italo Calvino in the fictional tales of his Invisible Cities, reflect the charm of a meeting of two cultures that are different in their forms and colours, but astonishingly alike in their fundamental values. If Kublai Khan and Marco Polo, in spite of being known around the world, are still only literary and mythical heroes, the Slovenes and the Chinese have real individuals who recorded in our joint history what is for us perhaps the most important encounter of East and West, as well as of their science and art, thus creating a link between our two countries that goes as far back as three hundred years ago. We are talking about the scholar Ferdinand Avguštin Hallerstein, also known as Liu Songling, a Slovene Jesuit who was invited by the Chinese Emperor Qianlong, an admirer of Western science and art, to his court, appointed by him as one of the leading astronomers and, because of Hallerstein’s wide language skills and knowledge, entrusted with diplomatic duties. Hallerstein received great honours and China, where he is buried, became his second home. Slovenia forgot him, but through the artistic vision of the multifaceted artist Huiqin Wang, who recognised in Hallerstein’s fate a part of her own destiny, his image once again takes shape.

The painter, illustrator and creator of graphic and calligraphic works Huiqin Wang comes from Nantong in China and has for over thirty years been living and working in Slovenia. She first attracted attention in the Eighties when, with technical perfection and rational use of form, she began unobtrusively introducing to the leading form of fine art in Slovenia at that time – graphic art – the poeticism of her domestic genius loci, calligraphy, and the centuries-old methods of painting and printing on hand-made paper and material. Throughout history Slovene art has been created in a small space, the crossroads of distant routes from the north, south and east, with the participation of travellers who only made a fleeting visit, but even more by those who found their second home here. Huiqin Wang was undoubtedly enchanted by this unique conglomeration of great Western European styles and by the heritage of local artists, for it was slowly creating a place for itself in the iconography and artistic perception characteristic of traditional Chinese art. Slovene art enthusiasts were no less taken, or perhaps even more so, by the half-abstract images of an almost fairy-tale nature, the transparent colours and the rich symbols perfected to the last character. This is one of the reasons why Wang has been particularly successful as an illustrator, where she can succumb to her imagination and at times barely noticeable nostalgia. Huiqin Wang is constantly aware that her personal and professional lives are determined by two homelands and two cultural traditions, as well as two artistic experiences, which she has recently been increasingly successfully combining into a semantically and formally new conceptual world.

Her latest project “Hallerstein: A Slovene in the Forbidden City” is the result of years of work and a unique synthesis of a passionate search through the archives for any factual information about the scholar’s life and work in China, and of the strikingly artistic tale of a man with two homelands into which her own personal story of a Slovene artist from China is also interwoven. The picture book is the first bilingual story about Hallerstein, with a handy glossary and, above all, brilliant illustrations that include a map and the astronomer’s drawings based on the original documents. The picturesque images covering the whole page, combining the fundamental principles of traditional Chinese painting with modern approaches, rooted also in her education in Ljubljana, reveal a true encyclopaedia of a particular place and time, for in addition to the Great Wall of China, the imperial palace with a multitude of courtiers, the observatory and even Confucius, there are numerous details in them where the narrator concealed her own special messages. Among these are the unusual angels with whom she peopled the sky above China, which are a symbol of Hallerstein’s religion and at the same time heavenly harbingers; they are usually holding musical instruments, which is why Huiqin Wang connected them with music, an ancient and respected art in China. The most intimate image in the book is undoubtedly Ljubljana at night, with the cathedral and Dragon Bridge. The sky is full of the stars that Hallerstein observed far away in Beijing while he perhaps thought about Slovenia. During such nights, when all is calm, our artist also looks at the starry sky with a feeling of homesickness, remembering her first home. It is then that she feels even closer to the Slovene scholar and in the shadowy images almost recognises his features, which she must paint and thus continue to tell her story about Hallerstein, about other people and places, and about China, but only in small instalments and through other stories so that its image does not fade away.

Judita Krivec Dragan

Vir: Mladinska knjiga